Reducing a household's energy consumption

Cost of living has become a real concern in the UK: Energy prices increased substantially (held at their current level only because the Government is using public finances to pay the difference), along with substantial increases in mortgage rates and the cost of basic staples.

As a country, the need for food banks has become normalised and even households on once-comfortable incomes are having to rely on them.

The recent change in Government is likely to help with some of the economic concerns, but many have been growing over the last decade, so the new government is unlikely to touch (let alone fix) most of the issues any time soon.

This seems especially likely given that, despite some initial hope, early signs are that the new Government is going to be no better than it's predecessors, having already re-appointed Ministers who've broken the ministerial code, along with those who seek to further erode our rights just hours after the Rishi Sunak told the nation his government would "have integrity, professionalism and accountability at every level".

I think James O'Brien sums that up quite well

Whether or not Sunak corrects that particular mistake, the forthcoming budget is expected to be brutal (with the government already being warned that some budgets just can't afford further cuts).

The World Bank has said that providing energy help for everyone is too expensive and that measures need to be targeted at those most in need. So, we can probably expect that the energy price cap will change to be means tested (in some way) when it comes up for review in April.

Needless to say, it's all feeling a bit bleak.

As an individual household, there's very little that can currently be done to influence events except watch the political horrors as they unfold.

Despite the Government's cap, most households are still paying significantly more for energy than they were (we're paying 3x more kWh than 18 months ago) and for many reducing usage is likely to be a top concern.

Unfortunately, there's quite a mish-mash of information on the net, with various "tips" that - at best - make your life a little harder, whilst not really saving a noticeable amount of energy. Human nature also tends to lead us towards things that are visible, but don't necessarily deliver much benefit.

In this post, I want to talk about some of those, as well as things that you can do to help bring your energy usage down.

Lighting

If you've got LED bulbs, each uses very little energy - a 3 Watt bulb will cost you about £1.90 a year. Yet, there are people out there who are expecting to have to go without electric light.

The perceived problem with lighting comes from two angles:

- it's (by design) a very visible form of usage, a light being on really stands out

- Many of us were brought up with the lesson that lights were expensive to leave on (because incadescent ones were), sometimes with grumbles like "it's lit up like the Blackpool illuminations in here".

Despite the low consumption of modern bulbs, a combination of these biases tends to lead to us overly focusing on reducing lighting costs because we don't fully understand what cost they entail.

As a matter of principle, it is still worth ensuring that lights are turned off when you're not using a room (unnecessary usage is still waste), but it's definitely not worth switching to candles or battery-operated lights instead (quite aside from the inconvenience, the batteries and the candles will cost more than the energy).

If you've still got Halogen or incadescent bulbs, it's definitely worth spending a small amount (you can even get them in Poundland) on some LED bulbs - there are calculators you can use to get an idea of the savings.

One other thing that I have found helpful, is having LED lamps come on at a specific time of day (I use HomeAssistant, but mechanical timers will work too).

The overhead light in our living room is a lovely wrought iron candleabra type thing, but it has a lot of bulbs in it, so although the individual draw of each bulb is low, the total consumption is quite high.

Timed LED lamps help discourage use of the more expensive overhead light fitting: if the room's already lit, it's less likely anyone'll hit the switch for the big light, and their consumption is sufficiently low that having them on (even when the room's empty) still consumes far less energy than shorter periods with the big light on.

New Appliances

Generally speaking, the majority of a gas-heated home's electric consumption is caused by appliances.

Switching to an A rated fridge might save quite a bit of energy, but it's not really a realistic suggestion for most households.

Buying more energy efficient appliances makes sense when existing ones need replacing, but buying new appliances in order to reduce your energy bills is fairly short-sighted. It can take a long time for energy savings to break even with the capital cost of purchasing the appliance, and the waste of an otherwise working appliance has it's own environmental impacts.

New appliances are an investment, and as such take time to yield returns. This means that they are zero use if your concern is affording energy bills this winter: you'd be better off setting the purchase cost aside and using that to help pay your bills.

Comparing Appliances

If for some reason, new appliances are on the cards, it's worth bearing in mind that not all appliances are created equally.

For example, in my post comparing Air Fryer Energy Use to an Oven I found that whilst it was more efficient than the oven, the air fryer's gains were extremely marginal.

However, the BBC have also since published a similar experiment, and observed much higher savings, despite their air-fryer consuming significantly more power than mine.

The reason for this difference in savings almost certainly comes down to the model of oven in use.

The BBC's article doesn't note what model of Oven was used (or, what temperature the food was cooked at), but it seems quite likely that it's not as well insulated as my (fairly high end) one.

The BBC's 35 minute cook consumed 1.05 kWh whilst my oven consumed just 0.343 kWh. Even accounting for longer cook times and higher temperatures, that's a significant difference in consumption. The heating element in their oven spent had to work much harder, suggesting that their oven was less able to retain heat than mine.

The lesson to take from this, is that when looking at posts and articles comparing appliance types, you should always take note of the models being tested, because findings with one model may not be applicable to others.

Eco mode

One of the easiest, and most obvious ways to drive savings is to make use of "Eco" mode on appliances: my dishwasher's Eco-mode consumes 42% less energy than a normal run.

However, "Eco" is not always the most cost-efficient setting.

On my washing machine, Eco mode takes over 3 hours and consumes 0.9 kWh. However, the machine also offers a 15 minute short-cycle, which consumes just 0.02 kWh, in part because it runs at 30 degrees rather than Eco's 40.

Note: If your washing machine is set to use low temperatures (particularly something like 20), think carefully about the washing solution you're using and whether it works at that temperature. Some powders can clump and block the machine's outlet, so try to prefer liquid detergent.

When working out the most cost efficient mode to use on an appliance, the two main things to consider are

- How long it runs for

- What temperature it needs to achieve

The longer something runs for, the higher it's power consumption (to the extent that a slow cooker consumes more energy than my oven does). Similarly, the higher a temperature it needs to achieve, or the greater the volume it needs to heat, the more energy it will consume.

Laundry

Whilst we're on the topic of Laundry, it can be quite a significant energy sink, particularly in winter:

- The washing machine uses energy

- The tumble dryer uses even more

- The iron uses a bit

As above, the overall impact of the washing machine can be reduced by reducing the wash temperature.

Drying is a little harder:

- It is possible to get electric drying racks, they're cheap to run, but expensive to buy (so you run into the issues around capital cost)

- A standard drying rack is cheap, though clothes will take longer to dry

However you chose to dry clothes, you need to ensure that you ventilate the house well, as the resulting increase in humidity can lead to mould and Aspergillosis.

If you've already got one, one other option is to use a rack and a dehumidifier - many dehumidifiers (and portable A/C units) have a "laundy mode". Dry air can absorb more moisture from the clothes, allowing them to dry faster.

Running a dehumidifer is quite energy intensive, but less so than a the tumble dryer, and helps to address worries about build up of humididty.

Reducing the (limited) energy impact of the iron is relatively simple: Hang stuff up instead of ironing it.

Brew Time

Although not a huge saving, one of the easiest savings that can be made is achieved by changing behaviour when filling the kettle.

A kettle's draw is high but short-lived, and it tends to be used multiple times a day.

The more water there is in the kettle, the more energy is required to bring in order to bring it to the boil.

In practice, boiling a full kettle costs around 5x more than boiling one filled only to the min line, so only boil the water that you intend to use.

Although reboiling a kettle may save a little energy, if you live in a hard water area, it's likely to cost you more in the long term than emptying and refilling with fresh water.

When you next need to replace your kettle, consider whether it's worth purchasing one with temperature controls

However, the suitability of these will depend on your drinking and usage habits.

With ours, I found that Black tea doesn't taste quite right at 80, and the kettle's primarily used for tea. On the other hand, if you're someone who commonly adds a splash of cold water to bring the temperature down, it may be that you're better off going for a lower temperature to begin with.

Fill The Fridge

When we bought the house, it came with quite a big fridge. It's very rare that we completely fill it with food, so there's a lot of unused space in there.

The problem with this is, every time you open the fridge door, warm air from the room rushes in, raising the internal temperature of the fridge, consuming more energy as the fridge works to bring it back down.

To help mitigate the effects of this, I've put blocks of polystyrene into the unused draws and door cubbys - each block offsets a volume of warm air, reducing the impact of the door being opened.

And, of course, it's worth breaking the habit of holding the door open whilst you look and work out what you wanted.

Heating

It's not uncommon to hear that you can save energy by turning the thermostat down by 1℃. It's hard to escape the feeling though, that at a certain point, you'll have turned it down so much that the heating won't actually turn on at all.

There are, however, other savings you can make without needing to freeze.

Smart heating systems such as Nest and Hive are all the rage, and claim to save energy/money by learning your habits/house and adapting to them.

Unfortunately, our NEST thermostat doen't seem to have lived up to those claims, and I've written before about how disillusioned I'd become with it

Nowadays our NEST thermostat is nothing more than a programmable thermostat with remote connectivity. Any "learning" functionality has been turned off to prevent it either burning gas unnecessarily, or turning the heating off on us because we had the temerity to watch a long film.

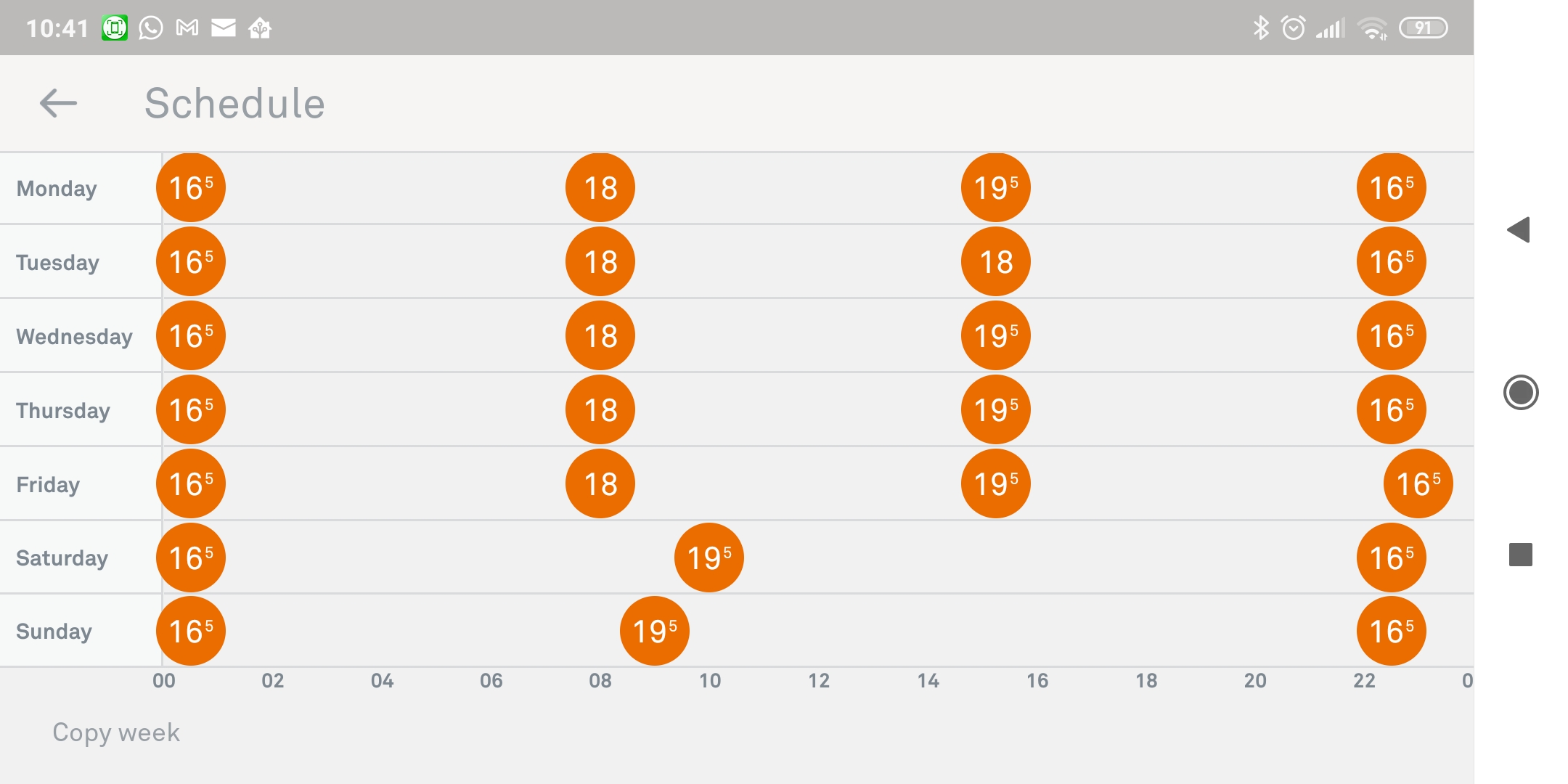

It turns out that that all we really need is to be able to set schedules, and to be able to call an API to collect stats or amend the temperature.

Having the ability to program the thermostat with a granular schedule really does help to achieve some energy savings.

Not only can the house drop to a more comfortable sleeping temperature overnight (using less energy in the process) but it can have the minimum temperature drop when appropriate. Since I took the screenshot above (back in 2020), I've since changed the heating to drop to 14 during weekdays, as most rooms don't need anything more than frost/mould prevention.

You can also buy programmable radiator thermostats (TRV heads) - I use these - which provide the ability to reduce the target temperature in specific rooms that are unused at specific times of the week. Between them, the heads I have in two rooms have shaved off about 167 hours of unnecessary potential heating time.

If you're going for full automation, you can get remotely programmable heads like these Zigbee ones, but at the time I found that the benefits didn't really outweight the (per-radiator) additional cost.

Removing the need to heat rooms (or the house) to a comfortable temperature when it's not needed can help to yield energy savings. Whilst they're heavily marketed towards this use-case, there's no need to spend out on something like NEST to achieve this - in fact, with the benefit of hindsight, if I were things over again I'd probably buy something like a Honeywell Wifi Thermostat instead.

Finally, if you have a water tank and are experiencing high bills - make sure your immersion heater hasn't been left switched on 24/7.

Base Load

Identifying high draw appliances is relatively easy, it tends to be a case of looking for things which involve heating (whether water or food).

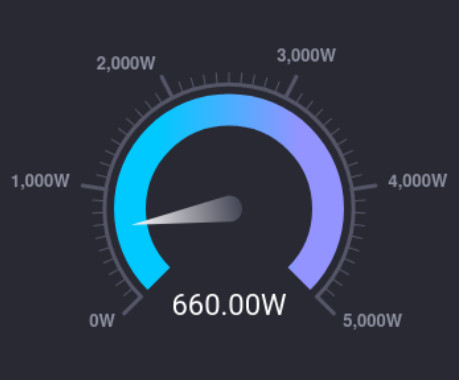

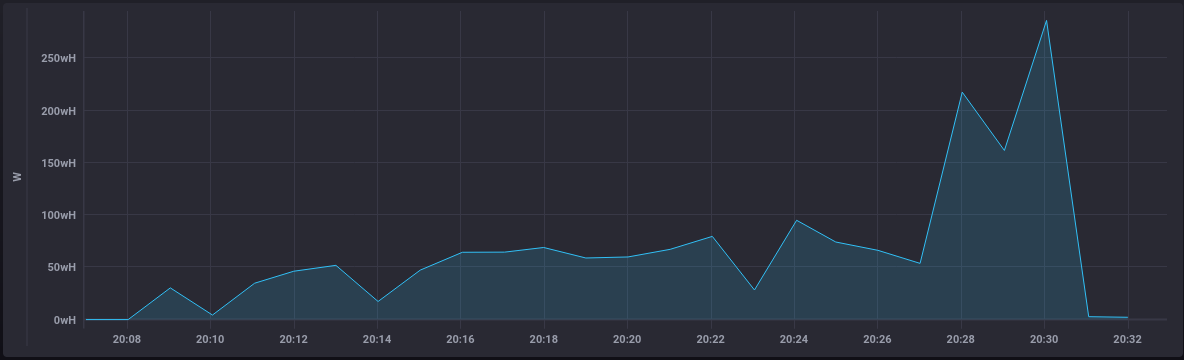

But, although their draw is high, those things tend to only be on for relatively short times. The rest of your routine usage will likely be driven by a lower, but near constant, sucking of power:

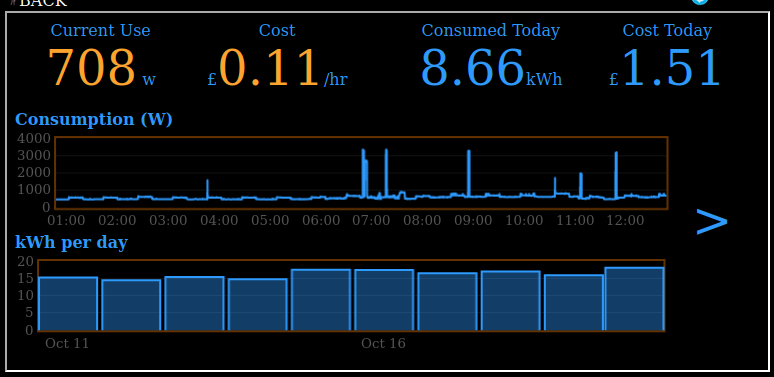

(ours is currently quite high, for various reasons)

Although it's helpful, you don't necessarily need to have an energy monitoring solution in order to identify sources of base-load.

You're interested in things which meet the following two criteria

- Things that are almost always on

- Things that don't need to always be on

For example, a fridge meets 1, but doesn't meet 2: turning your fridge off periodically will save energy, but will also very likely lead to food poisoning.

However, a pond pump might meet both points (depending on what the pump is for: if it's the filtration system for a Koi pond, you'll want to keep it on. If it's just a waterfall, a timer might be in order).

Similarly, if you live in a household where the TV seems to be on, regardless of whether there's anyone in the room, you might be able to cut the base load by a couple of hundred watts by simply turning it off.

Although devices left on standby don't generally consume much energy, with lots of devices, that combined usage can add up.

Although it's standard advice, it's simply not realistic to say that everything should be turned off at the wall every time. You'll likely manage that for the first week, and then slip back to using standby (especially as things like smart TV's take forever to do a cold boot).

It's much more practical, and useful, to try and identify devices that are almost permanently on standby (i.e. they're there, but not actually being used regularly) as unplugging those removes their usage with almost no impact on your day-to-day life.

It's much more reasonable to expect yourself to unplug a TV in an unused room once than it is to need to do it in the living room daily.

Beyond a certain point, reducing base load is hard, because you ultimately reach the point that the only way to reduce further is to remove or replace appliances (see above for the issues with that).

Throwing Tech at it

This isn't essential, but if you've the ability and the inclination, using tech to track and control usage can be quite beneficial.

You don't need to have a smart meter to track usage (and, in fact, there are a number of good reasons you might not want one, including the fact that they contain a contactor allowing remote cut-off of your power, accidentally or otherwise).

I use a clamp meter to track usage at the meter, as well as using a selection of smart sockets to track usage of individual appliances.

There are various off-the-shelf solutions which can be used too.

If you do have a smart meter, you may have noticed that the sample frequency in your supplier's portal is pants. The meters only send readings every 30 minutes or so, which is better than nothing, but really not particularly useful for working on consumption.

However, you can buy a new In-Home-Display (IHD) for them which will send readings via MQTT - RevK has a good write up of doing exactly this.

I write usage stats directly into InfluxDB, HomeAssistant to control things like lights, and a home built IHD to display recent usage stats

Even a simple solution, like using the Kasa or Tapo apps to create automations can be helpful - whether that's turning some cheap lamps on at a set time, or going all out and linking lights to motion sensors.

Insulation

The very best change you can make, is to ensure that your attic is properly insulated - current specs recommend 270mm of insulation.

The graph below shows our average daily gas usage over two winters

The second was after I'd properly insulated the attic (having received the bill for the first) and peaks at a little over half the peak of the previous year.

Insulation is relatively cheap, and can usually be self-installed (though it's a horrible, dirty, itchy job). Once in, it helps the house retain heat so you have to use less energy replacing losses.

Bad Shouts

There are a few peculiar bits of advice I've seen on the net from time to time.

None of these are a good idea, even if they sound like they might save energy, they'll do so at the cost of your health, or much bigger costs over time.

- Turn the immersion heater right down: although it'll save energy, stored water needs to be heated to 60c periodically to ensure that legionella does not develop.

- Turn the heating off completely: not only do you run the risk of frozen and burst pipes, but there will likely be a high level of condensation in the house, leading to mould growth, and potentially result in health issues like Aspergillosis.

- Turn the router off overnight: the savings are absolutely minimal, and if you're on ADSL the constant interruptions to connectivity might lead to worse broadband performance

- Not turning the cooker extractor fan on: It's true that the extractor fan pulls out heat that would otherwise remain in the house, but it also extracts carbon monoxide (if you're using gas) and burnt byproducts (from detritis inside the oven, or around the hob), both of which can cause serious health problems.

- Not turning the shower extractor on: just like the oven extractor fan, the bathroom fan pulls heat out of the room. However, it also pulls humidity from the shower, preventing condensation, mould and illness.

- Leave the oven door open: There's advice suggesting that if you leave the oven door open after cooking, you'll let heat out into the house, reducing your heating bill. Leaving the door open, though, only really puts you (and your kids and pets) at risk of a burn. Heat doesn't simply disappear, the heat from the oven will dissipate into the house whether or not the door is left open - all that changes is the rate at which it does so.

-

Buy a more energy efficient X: in the short term, purchasing new appliances only makes financial sense if the original needs to be replaced. If you're looking to reduce cost over the next

yyears, it makes sense, but it won't help you this winter, because you'll have had to find the money for the purchase in the first place. The exception to this is bulbs - replacing incandescent bulbs with LED can break even quite quickly. - Use candles instead of lights: it is sometimes nice to curl up by candlelight, but around 4% of house fires (and deaths) start with candles, so doing so routinely is ill-advised. It's tempting to say that humans used to live by candlelight alone, but Victorian houses had a lot of fires. Financially, a LED bulb will cost less than candles, and is far less likely to burn the house down. If you are going to use candles, observe the safety guidelines

Portable Gas Heater

Although not quite worth of being added to the "bad idea" list, a special mention does need to go to the suggestion of using portable gas fires for heating. The idea is that the bottle is a fixed cost, so there will be no surprise bill at the end.

Having a portable gas fire around for emergencies is prudent - especially given the possibility of blackouts this winter.

However, using it as a replacement for heating is problematic for a number of reasons

- The gas is much more expensive to purchase that way

- Calor aren't currently allowing new contracts of certain bottle types, so you may struggle to get a bottle unless you have an old one to exchange

- There's a risk of Carbon Monoxide poisoning from extended use in insufficiently ventilated rooms

- Burning gas creates (amongst other things) water - so humidity will increase in the building

If a portable gas heater is being used, at the minimum, the room should be properly ventilated (by opening doors/windows) every few hours, and an audible Monoxide detector should be used, and the fire should never be left on whilst sleeping.

Conclusion

It's been a while since I've posted a free-form article, so it has turned into a bit of a ramble in places.

There are a lot of things which can be done in order to achieve meaningful energy savings, the problem is that they're not always obvious - we tend to be drawn towards more visible examples of usage, rather than to things that are responsible for real cost. We tut at lights left on in empty rooms whilst collecting clothes that'll be washed at 60℃

There's also a lot of logical-sounding, but bad, advice out there.

Pumping heat out of your house with an extractor fan sounds like an unnecessary action, but it's important to consider why it's being done - it isn't normally heat that the extractor's there to remove, but combustion by-products and moisture, the presence of which can lead to serious health concerns.

The very best savings often come through changes in behaviour, but those can be very difficult to maintain over long periods, so should always be accompanied by things which either don't require significant change or help to support the changes you're trying to achieve. For example, using timers to automate LED lamps so that the more expensive lights don't get switched on as much and unplugging devices which spend most of the month/week in standby.

Longer term changes like appliance replacements are possible, but are likely to be of little help this winter, and many involve spending money that could be used for bills and food.

Aside from purchasing new appliances, and insulating your home, the very best investment you can make in your long-term costs is not to vote Tory at the next election - they've been in power for over a decade and energy and economic policy has been mishandled, if not outright neglected, in favour of ideological arguments and culture wars. It was, unfortunately, inevitable that the country would reach this point, and you and I now get to carry the cost of that (not to mention the Tory premium on mortgage payments).